DISCOVERING THE LYMPHATICS

The widespread lymphatic vessels in the body are difficult to see and escaped proper study for centuries. These delicate, thin-walled vessels bring intestinally absorbed fat and tissue fluid from all parts of the body back to the general circulation, providing immunologic and antibacterial functions as they pass through numerous lymph nodes. The first to describe lymphatic vessels in some detail was Galen, the famous second-century Greek-Roman physician. During animal dissections he saw lymph nodes, that he considered “cushions” to protect organs, and described slender vessels running between abdominal lymph nodes and the intestines. In Galen’s concept of circulation, the liver manufactured blood that flowed in veins out to the intestines and other peripheral sites, nourishing them, while “spiritous” blood also flowed peripherally through arteries. The blood was absorbed in the periphery; it did not circulate back.

Andreas Vesalius, the great sixteenth century Belgian anatomist, still anchored to Galenic physiology, had a similar conception. Like Galen, he saw the tiny abdominal vessels without blood (lymphatics) leading to the liver, believing they connected to a portal vein that flowed bidirectionally, in part carrying chyle to the liver to aid in making blood.

By the early decades of the next century, experimentation to

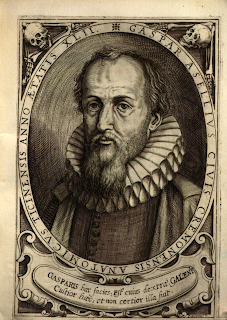

Gaspare Aselli (Wikipedia)

establish knowledge, as opposed to genuflecting to ancient teachings, had come into vogue. In this vein, Gaspare Aselli, professor of anatomy and surgery at the University of Pavia, on July 23, 1622, dissected a dog for two colleagues who wanted to see the “recurrent nerves.” Pressing down on the intestines to view the diaphragm, he noticed in the mesentery “numberless fine white cords.” He thought they were nerves but on cutting one he saw a milky fluid emerge. When he opened another dog and could not find the vessels he remembered that the first

Woodblock print from Aselli's 1627

De lactibus, sive lacteis venis, quarto vasorum

mesaraicorum dissertatio (Wikipedia)

The slender white lines are lymph vessels passing

through the mesentery.

dog had eaten before the dissection. He soon proved that the tiny vessels indeed carried fat-laden fluid (chyle), absorbed after meals, through the mesentery toward the liver where he assumed they terminated, supplying nutrients for blood formation according to Galen’s scheme.

Aselli died three years later, at age 44. Two of his colleagues, Alessandro Tadini and Senatore Settala, published his findings in 1627, one year before William Harvey’s publication on the circulation of the blood, a publication that shed doubt on Galen’s teaching of the liver as the source of blood.

Did these chylous vessels exist in humans? Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, a wealthy senator in Provence and supporter of science, “caused a man which was condemned to be hanged to be fed lustily and securely before sentence was pronounced….and an hour and a half after he was turned off, he caused the Body to be brought into the Anatomical Theater.” (Gassendi). There de Peiresc found similar chylous vessels emerging from the intestines.

The picture of the lymphatic circulation was still incomplete. The Dutch anatomist, Jan de Wale (Johannes Walaeus) established, using ligatures of portal and lymphatic vessels, that the portal veins carrying blood from the intestines were distinct from the lymphatic vessels carrying chyle. He communicated these findings to Thomas Bartholin, who published them in 1641 and in enlarged form in 1645 in his anatomy text, Institutiones Anatomicae. Bartholin was one of Europe’s most

Jan de Wale (Wikipedia)

Thomas Bartholin (Wikipedia)

distinguished anatomists, based in Copenhagen.

The liver remained the perceived endpoint of lymphatic flow, however, until animal dissections by the French physician Jean Pecquet found that chylous lymph from the intestines actually bypasses the liver, runs to a sac that gathers lymph (the cisterna chyli) and then rises through the thorax via the thoracic duct, a vessel that carries the lymph to the bloodstream. In short, the liver is not nourished by lymph.

Illustration from Picquet's Experimenta Nova Anatomica showing the chyli receptaculum

(cisterna chyli) labeled "I" and thoracic ducts above. (Internet Archive) Click on image to enlarge.

Thomas Bartholin extended these observations and summarized the findings in 1653 under the title Vasa Lymphatica, Nuper Hafniae in Animantibus inventa, et Hepatis Exsequiae. The last two words translate as “obsequies of the liver,” a piece of humor by which he meant to convey the death of Galen’s teaching of the liver as the source of blood.

Bartholin's Vasa Lymphatica

(Internet Archive)

Unbeknownst to Bartholin and Pecquet, a Swedish medical student, Olof Rudbeck, while dissecting a calf, had noticed “whey-like fluid” emanating from its upper thorax. He eventually traced out much of the lymphatic system, including, for the first time, the myriad vessels from the periphery, again showing that no lymph drained into the liver. In April 1652 he demonstrated his findings before Queen Christine and in May defended a thesis on the subject, published in 1653. He learned about Bartholin’s publications later that year and in 1654 a Leiden publisher produced a book containing publications of Pecquet, Bartholin, and Rudbeck. Rudbeck claimed that for this book Bartholin had backdated his work to 1652 (It is not certain this is true).

Olof Rudbeck (Wikipedia)

A priority dispute arose between Rudbeck and Bartholin, fought out bitterly in various pamphlets and publications. Bartholin largely abstained from the quarrel as his supporters fanned the flames. One scholar who has studied the controversy, Charles Ambrose, credits Pecquet with discovering that abdominal lymph vessels bypass the liver to the thorax and the bloodstream, and Rudbeck with the discovery of the wider system of lymphatic drainage. In Rudbeck’s day, the public presentation of a scientific finding, such as before the Queen, was viewed as a date of communication. Rudbeck was a gifted scholar who taught several subjects and at age 31 was appointed rector of the University in Upsala. He used the name vasa glandularum serosa to describe the lymphatic system, but Bartholin’s vasa lymphatica is the name that survived in English as lymphatic vessels.

The wonders of the lymphatic system are still unfolding, in particular its immunological functions.

SOURCES:

Suy, R, et al, “The Discovery of Lymphatic System in the Seventeenth Century: Part I: the Early History.” 2016; Acta Chirurgica Belgica 116 (4): 260-66 and "Part II," 116 (5): 325-331.

Park, J and Riva, M, “Gaspare Aselli (1581-1625) and Lacteis Venis: Four Centuries from the Discovery of Lymphatic System.” 2023; Amer Surgeon 89 (6): 2325-8.

Gassendus, Petrus, The Life of the Renowned Nicolaus Claudius Fabricius Lord of Peiresk, Senator of the Parliament at Aix. 1657, London.

Natale, G, et al, “Scholars and Scientists in the History of the Lymphatic System.” 2017; J Anatomy 231: 417-29.

Leeds, S, “Three Centuries of History of the Lymphatic System.” 1977; Surg Gyn Obs 144: 927-34.

Guerrini, A, “Experiments, Causation, and the Uses of Vivisection in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century.” 2013; J Hist Biology 46: 227-54.

Tonetti, L, “The Discovery of Lymphatic System as a Turning Point in Medical Knowledge: Aselli, Pecquet and the End of Hepatocentrism.” 2017; J Theoret Applied Vascular Research 2(2): 67-76.

Ambrose, C, “Immunology’s First Priority Dispute – An Account of the 17th Century Rudbeck-Bartholin Feud.” 2006; Cellular Immunology 242: 1-8.

A full index of past essays is available at:

https://museumofmedicalhistory.org/j-gordon-frierson%2C-md