Muscles’ Monikers Through Time

by Roy A. Meals, MD

While interest in and knowledge of anatomy increased steadily during the Renaissance, differentiating and naming the newly observed muscles proceeded with fits and starts. True, more than a millennium before, Galen had described muscles by their location and function, but he did not actually name them. For instance, “Two of the muscles on the inner side of the forearm…flex the fingers,” and “The next largest…flex the whole wrist,” are examples, obviously confusing to a student embarking on his first anatomical studies.

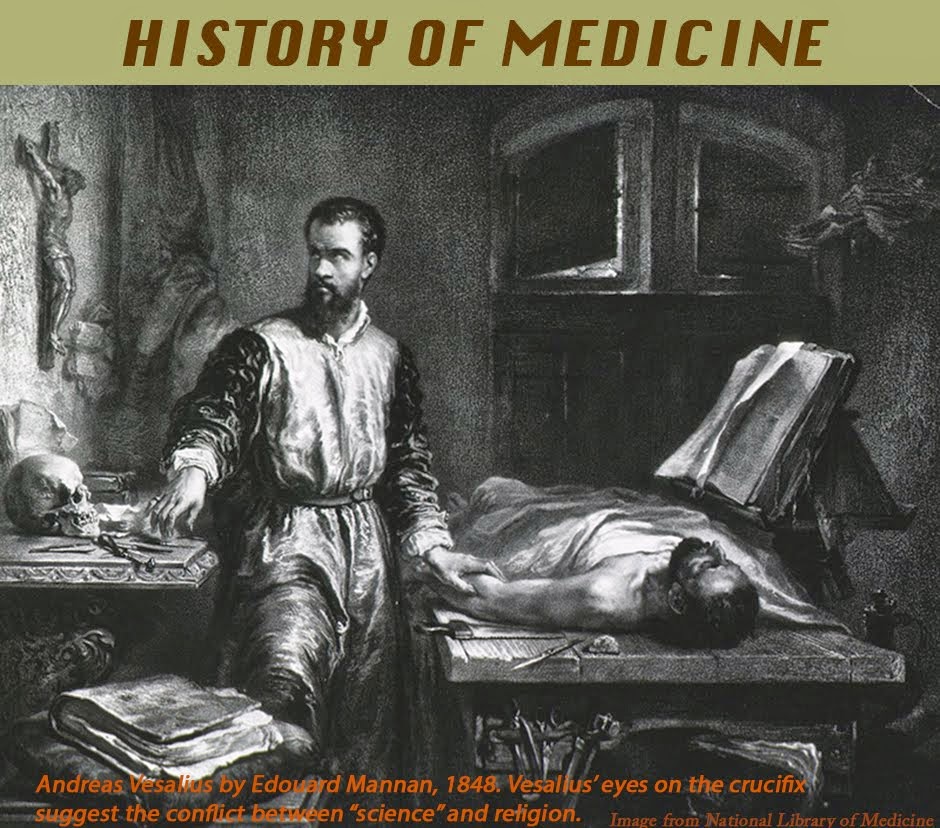

Vesalius (1514-1564) tended to number all anatomical structures and cross-referenced them in the text and drawings of his seminal Fabrica (1543). In addition to naming two jaw muscles and the six-pack, Vesalius also named an arm muscle the anterior cubitum

Andreas Vesalius by Jan van Calcar, the artist who

made woodcut prints for Vesalius (Wikipedia)

flectentium musculus—though it seems, in this case, a nice succinct number would have been more user-friendly. Had all the muscles retained numbers, however, it could get cumbersome. For instance, somebody might ask you to flex your number 489 and you couldn’t remember which one it was, out of the roughly 650 that humans have.

One of Vesalius’s teachers, Sylvius (1478-1555), in Hippocrates et Galeni physiologicae partem anatomicam isagoge (Anatomical Introduction) (1555), named many anatomical structures, especially vessels and muscles “for the sake of brevity and the perspicuity of thing.” Possibly because Sylvius did not illustrate his work, his terminology did not catch on. Fifty years later, Bauhin (1560-1624) rekindled interest in descriptive terminology by referring readers of his unillustrated Theatrum anatomicum (1605) to Vesalius’s depictions in Fabrica. After that, naming proceeded in full force over the next 300 years.

Many anatomists pitched in and gave the muscles descriptive names and fortunately renamed the anterior cubitum flectentium musculus the biceps. Some of the original names were outright poetic. Consider, for instance, the contributions of Jan Jesenius (1566–1621), a Bohemian physician, politician, and philosopher. He was professor of anatomy in Wittenberg and later at Charles

Jan Jesenius (Wikipedia)

University in Prague, where he also performed the city’s first public autopsy, an event said to have attracted 1000 onlookers. He named the muscles controlling the eyeball’s movement amatorius (muscle of lovers), superbus (proud muscle), bibitorius (muscle of drinkers - contraction of the medial rectus muscles would make one cross-eyed), indignatorius (muscle of anger), and humilis (muscle of lowliness). Twenty years later, early in the ThirtyYears War, Jesenius was executed for his Protestant views rather than his muscle naming. It is too bad that in 1895 anatomists standardized the nomenclature and dully renamed the eye muscles according to their location (superior, inferior, medial, lateral) and alignment (rectus [straight] and oblique).

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the language in anatomical tomes began to move away from Latin to modern languages, confusing the terminology in a different way. In addition, new “systems” were proposed, such as that of Monro in Scotland and Francois Chausser in France, who both proposed a new terminology for muscles based on their sites of origin and termination. A few muscles’ names do identify their origins and insertions. For instance, the sternocleidomastoid is the strappy muscle on the side of the neck that turns your head to the side. One end attaches to the breastbone (sterno) and collar bone (clavicle, cleido) and the other end fastens to the mastoid process of the skull, which is palpable just behind the earlobe. By the nineteenth century, anatomists had identified and named nearly everything, but often with multiple synonyms first in Latin and later in more modern languages. In a non-muscular example, one author in 1917 listed 16 names for the pineal body, including “parietal eye” and “penis cerebri.” Anatomists and clinicians came to recognize that this towering Babel of terminology should be simplified to have clear meaning, logical consistency, and compact form.

The German Anatomical Society began the reform process in 1887. The prominent Swiss anatomist Wilhelm His, Sr. (his son, W.

Wilhelm His, Sr. (Wikipedia)

His, Jr., described the bundle of His) spearheaded the effort, forming a committee of prominent anatomists that in turn consulted anatomists from several countries. In 1895 their efforts coalesced into the Basle Nomina Anatomica (BNA), the first compilation of standardized anatomical names, written in Latin. Several revisions have ensued.

Some muscles received names of objects they resemble. Piriformis, a hip muscle, is pear-shaped. The deep calf muscle, the soleus, is sandal-shaped. Overlying it is the bulgy gastrocnemius, literally the belly of the leg. In each palm and sole are four worm-shaped muscles, lumbricales manus and lumbricales pedis, respectively. The Latin name for earthworm is Lumbricus.

Illustration from the Basle Nomina Anatomica, 1895 (Internet Archive)

Other muscles received names according to their location, such as the subclavius (under the clavicle) and the intercostales externi (external layer, between the ribs). The number of parts determines a few labels: Bi- means two, and the biceps has two origins, one from the shoulder blade, one from the upper arm bone. The triceps has three origins, and the quadriceps has . . . well, guess. Length is another determinant. Thumb in Latin is pollux, and it has two muscles that fold (flex) the thumb across the palm—the flexor pollicis longus and flexor pollicis brevis. And a muscle’s action may determine the name; the cremaster, which lifts the testicle, derives from the Greek for “I hang.”

(Courtesy of Roy Meals, Wikipedia, and British Library)

Revisions of the nomenclature continued. In 1950 the newer International Anatomical Nomenclature Committee (IANC) took over the job. It was succeeded by the International Federation of Associations of Anatomists (IFAA) that issued, in 1998, its Terminologia Anatomica, containing both Latin and English versions of nomenclature.

In today’s world where schools, buildings, and military bases are receiving new names after second thoughts on their historical origins, one wonders what monikers future committees will bestow on muscles and other anatomical structures.

References

Buklijas, Tatjana: “The science and politics of naming: reforming anatomical nomenclature, ca. 1886-1955.” Journal History Medicine Allied Sciences. 2017;72(2):193-218

Eychleshymer, Albert C.: “Anatomic Nomenclature.” JAMA 1915;64(19):1569-1570.

Harrison, R. J., and E. J. Field. Anatomical Terms: Their Origins and Derivation. Cambridge: W. Heffer and Son, 1947.

Musil, Vladimir et al: “The history of Latin terminology of human skeletal muscles (from Vesalius to the present).” Surg Radiol Anat. 2015;37(1):33-41.

Sakai, Tatsuo: “Historical evolution of anatomical terminology from ancient to modern.” Anatomical Science International, 2007;82:65-81.