CHOLERA BEFORE ROBERT KOCH

Cholera outbreaks today are confined to areas of famine, war, or other sites of public health disarray. Though an old disease in India, it is a relatively new disease from a global viewpoint. The first recorded pandemic, that of 1817, marched from India eastward through Asia and westward to Persia and the Caucasus, but spared Europe.

In the next pandemic, beginning in 1829, cholera reached Russia, swept down through Europe, and traveled across the Atlantic to the United States, Canada, and South America, killing hundreds of thousands during its march. Western medical skills were powerless. Arguments raged over whether it was contagious or came from

|

| French drawing, cholera (Wikipedia) |

miasmas and/or foul air, and how to treat it. Quarantines of various types were debated and instituted irregularly. Galenic ideas, especially those involving corrupted humors to explain symptoms, still prevailed in medical thought. Accordingly, for treatment medical opinion favored measures to rid the body of corrupting material.

The losses of fluid in cholera are dramatic. Liters can be passed in liquid stools in a few hours, exacerbated by vomiting. Records describe patients as cadaveric, with dry, cold, grayish skin, near-absent pulse, and inaudible heart sounds. Blood from a vein or artery, if it came at all, resembled tar. Claude Bernard even suggested that survivors passed through a form of suspended animation similar to hibernation. It is obvious today that replacement of fluid is essential, but that was not so in the 1830s. Bleeding and purging were highly recommended treatments. Since blood was hard to extract, doctors often resorted to an artery to obtain small amounts of tarry material. Emetics, purgatives like calomel, cupping, and blistering were also part of regimens that did more harm than good.

Investigators in Moscow in 1830 were among the first to discover the high hematocrit and low water content of blood in cholera patients. Scattered reports of injecting water or saline solutions intravenously appeared, but results were disappointing. Inadequate amounts of fluid, injection of air bubbles, and bacterial contaminants all contributed to poor results, delaying intravenous fluid therapy until the twentieth century. Attempts to suppress bowel movements with opiates also met with little success.

A third pandemic lasted from 1845 to 1856. By then, contaminated water was under suspicion. John Snow’s surmise of a “cholera poison” in the water from a certain London water company and from a particular well resulted in removing the handle from the

|

| John Snow (Wikipedia) |

Broad Street pump in 1854. But the epidemic was already subsiding and the medical world paid relatively little attention. The “discovery” of the causative agent by an Italian microscopist also brought little reaction.

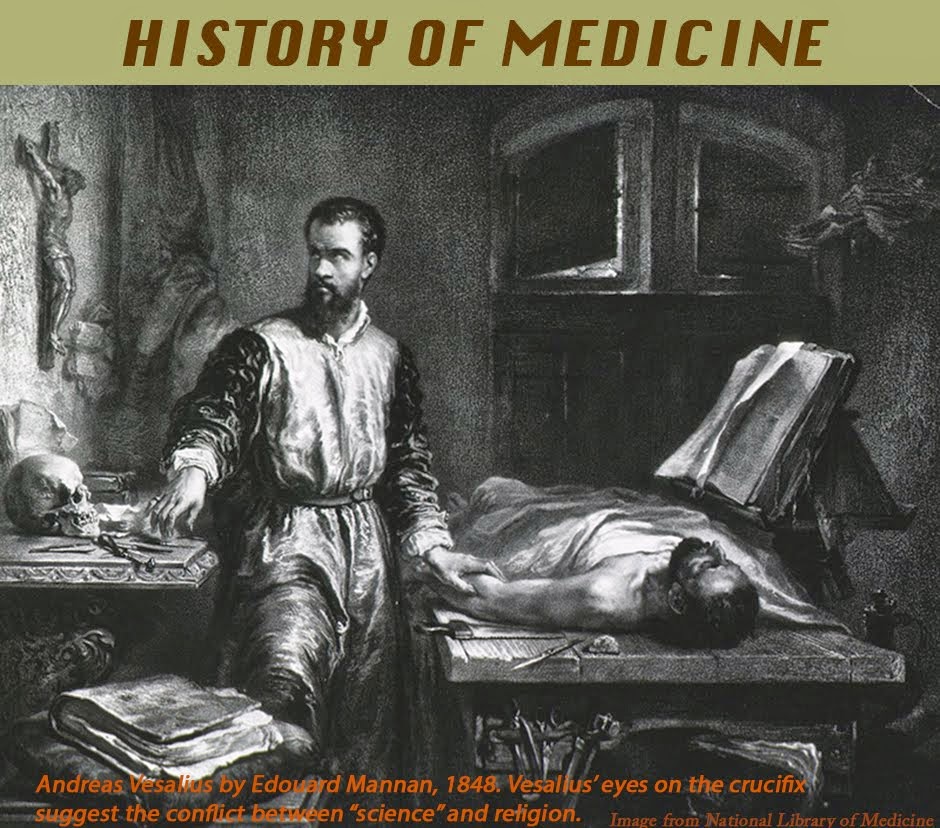

Filippo Pacini, son of a cobbler, received his medical education in Pisa. As a student, using a rudimentary microscope, he was the first to describe the tiny “Pacini” tactile dermal corpuscles, work later confirmed. His proficiency with the microscope catapulted him to the professorship of anatomy at the University of Florence. During the same pandemic that struck Snow’s London, Pacini studied cases in Florence using his microscope. He

|

| Filippo Pacini (Wellcome Library) |

noted disruptions of the intestinal mucosa and myriads of comma-shaped bacteria in the intestinal fluid. He published his findings in 1854 in an Italian journal, suggesting that the organisms caused the disease. He sent copies of his findings to the French Académie des Sciences, to Virchow, Henle, and Max von Pettenkofer in Germany. Reports also went to authorities in England, and to the Medical Society of London, where Snow was a member. Snow and Pacini never met, and it is not clear if Snow knew of Pacini’s work. Snow died in 1858 and a brief obituary in Lancet did not mention his work on cholera epidemiology.

Cholera struck Florence again in 1865. This time Pacini’s writings attracted the attention of William Farr, the British Registrar-General, who described Pacini’s findings in a report of 1868, including his insight that excess fluid loss was the cause of vascular collapse. Pacini recommended fluid replacement and developed complicated mathematical models to measure the fluid balance. Pacini’s writings, however, did not appreciably affect general medical opinion. It was too early. Lister’s first article on bacteria in wound infections appeared in 1867, was received skeptically, and Robert Koch first proved the bacterial cause of a disease (anthrax) only in 1874.

Max von Pettenkofer, the great German pioneer in public health

|

| Max von Pettenkofer (Wikipedia) |

science, explored cholera extensively. Having studied Snow’s work, he investigated water provisions in Munich and concluded that Munich’s water supply was not the problem. He went on to develop a cholera theory that required three factors to cause disease: the presence of live organisms (not yet discovered), proper soil conditions where the organisms can develop, and a susceptible host.

Finally, in 1884, Robert Koch “discovered” again the offending

|

| Robert Koch's Egyptian team. Koch is 3rd from right. (Wikipedia) |

organism during a trip to Egypt. He does not seem to have known about Pacini’s work. As the leading bacteriologist of the time, Koch was able to culture the vibrio and study its properties, techniques unavailable to Pacini. Though Pettenkofer accepted Koch’s findings, he was so assured of his soil development theory that he swallowed a pure culture of cholera vibrio, sustaining only mild diarrhea. A couple of his students who tried it, though, suffered from severe cholera.

In India, David D. Cunningham, an army doctor in charge of cholera research, was a follower of Pettenkofer and continued to

|

| David Cunningham (Wikipedia) |

resist Koch’s thesis of direct transmission for years. But accumulating evidence overcame the last doubters and solidified the modern view of cholera transmission, pathology, and treatment. Today the disease is primarily a feature of a breakdown in water supplies and hygiene.

SOURCES:

Isaacs, J D, “D D Cunningham and the Aetiology of Cholera in British India, 1869-1897.” Medical History 1998; 42: 279-305.

Carboni, G P, “The Enigma of Pacini’s Vibrio cholerae Discovery.” J Medical Microbiology 2021; 70 (11): 1-7.

Pettenkofer, M, “Nine Propositions Bearing on the Aetiology and Prophylaxis of Cholera, Deduced from the Official Reports of the Cholera Epidemic in East India and North America.” Indian Medical Gazette 1877; April 2, May 1, July 2, and August 1.

Howard-Jones, N, “Cholera Therapy in the Nineteenth Century.” J History of Medicine 1972; 27: 373-95.

Pollitzer, R, Cholera 1959; WHO, Geneva.

Evans, A S, “Pettenkofer Revisited: The Life and Contributions of Max Pettenkofer (1818-1901).Yale J Biol Med 1973; 46: 161-76.

Vinten-Johansen, P, et al, Cholera, Chloroform, and the Science of Medicine: A Life of john Snow. 2003; Oxford Univ Press.

A full index of past essays is available at:

https://museumofmedicalhistory.org/j-gordon-frierson%2C-md