ANATOMY IN PHILADELPHIA AND SIAMESE TWINS

In 1906, Franklin Mall, professor of anatomy at Johns Hopkins during the time of William Osler and William Halsted, gave a speech to the Association of American Anatomists, of which he was president. In reviewing the history of anatomy in America he said, “More than a century ago the status of anatomy in America compared favorably with that in Europe.” He signaled out the University of Pennsylvania, where anatomy instruction began in 1765. The first professor was William Shippen Jr., followed by Caspar Wistar. Wistar had studied in England and Edinburgh, wrote the first American textbook on anatomy, and provided a valuable collection of wax-injected preserved anatomic

|

| Caspar Wistar (Wikipedia) |

Last in the illustrious line of anatomy professors was Joseph Leidy, “the greatest teacher of anatomy to medical students this country has seen (Mall).” Leidy was professor of anatomy from 1853 until his death in 1891. By then the Wistar and Horner Anatomy Museum was aging. It was rescued in 1892 by Caspar Wistar’s great-nephew, Isaac Wistar, a general in the Civil War who had become wealthy in the railroad business. He built a new facility, the Wistar Institute for Anatomy and Biology. The Wistar Institute is still active today in a broad array of scientific endeavors.

In 1874, a unique anatomic specimen became available to anatomists and surgeons in Philadelphia. The famous Siamese Twins, Chang and Eng, the source of headlines for years, had died. The Siamese Twins were born on a riverboat in southern Thailand in 1811. The mother was of mixed Chinese-Thai heritage, the father was Chinese. They were joined at the sternum with a band of tissue that in adulthood measured about five inches in length and eight inches in circumference. The twin on the right, Chang, was slighter in

|

| The Siamese Twins, painted by Édouard Pingret 1836 (Wikipedia) |

development than Eng and had a more irritable personality. A Scottish roving businessman and a ship captain brought them to America as teenagers and exhibited them as “freaks” for several years, netting their “owners” handsome profits. After one partner cashed out and the other died, the twins exhibited themselves for several years, then settled in North Carolina, where they purchased a farm to raise tobacco, married a pair of white sisters, and fathered twenty-one children. They purchased slaves to work the farm.

In 1870, on a return trip from Europe by ship, while playing chess with the son of a fugitive slave, who was now president of Liberia, Chang developed a right hemiplegia. Four years later Chang developed a chest infection and died during the night. When Eng woke up and learned that his brother was dead, he too passed on quietly a few hours later.

On hearing of their death, Joseph Pancoast, a Philadelphia surgeon, telegraphed an inquiry about performing an autopsy on the twins. Pancoast was head of the anatomy

|

| Joseph Pancoast (Wikipedia) |

department at Jefferson Medical College, had taken over the editing of Wistar and Horner’s anatomy text, and was known for his extensively illustrated surgery text. Dr. Joseph Hollingsworth, the twins’ personal physician, felt that burying the twins locally would invite grave robbers. Rumors of a reward for the body were already circulating.

With assent from the family, Pancoast and Harrison Allen, professor of comparative anatomy at the U of Penn, came to their home, embalmed the bodies with zinc chloride solution, and shipped them to Philadelphia for an autopsy.

Philadelphia, a prominent medical city and for many years a leader in anatomical studies, was an appropriate choice. The city boasted five medical schools, was home to the American College of Physicians and was the site of the founding of the AMA in 1847.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital 1755 (Wikipedia) |

Joseph Leidy, the “greatest teacher of anatomy,” chaired the above-mentioned U of Penn anatomy department. Joseph Pancoast, chairman of anatomy at Jefferson, was described as a gifted operator with “hands as light as floating perfume.” The great Samuel Gross was chairman of surgery at Jefferson and was to have his portrait painted the following year by Thomas Eakins in “The Gross Clinic.” S. Weir Mitchell practiced in the city as a celebrated neurologist and novelist and the famous Mütter Museum, a gift of the surgeon Thomas Mütter, had opened.

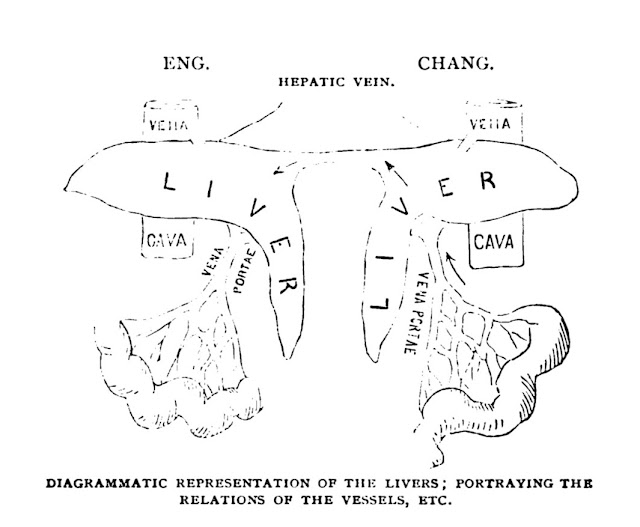

The findings of the limited autopsy on the twins were reported during a meeting at the College of Physicians. The family permitted only the posterior aspect of the band to be opened, along with limited abdominal incisions. The major findings were that the twins shared liver tissue through the connecting canal, that their respective peritoneal membranes overlapped each other in the canal but remained separate, and that umbilical arteries terminated feebly at the entrance to the band (the umbilicus was considered shared in the center). Dye injected into the portal circulation on Chang’s side emerged on Eng’s side.

|

| (From the article referenced below) |

During life it had become clear that the two arterial circulations and nervous systems were distinct. When Chang became intoxicated Eng did not, and if Eng ate asparagus only his urine smelled of it later. Similarly, if the center of the connecting band was pricked, they both felt pain, but not if pricked closer to their respective bodies.

The autopsy satisfied the doctors’ curiosity but did not open any new doors. The bigger lesson, it seems, was that two conjoined individuals could tolerate each other for 63 years.

SOURCES:

Huang, Yunte. Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and their Rendezvous with American History. 2018; Liveright.

Report of the Autopsy of the Siamese Twins. (Reprinted from the Philadelphia Medical Times), 1874. Available on Hathi Trust.

Mall, F P. “On Some Points of Importance to Anatomists.” 1907; Science 25(630): 121-5.

Savitch, S L, et al. “Joseph Pancoast, MD (1805-1882): The Surgeon Who Brought Anatomy to Life.” 2020; The American Surgeon. (online only)

Rutgow, I. “American Surgical Biographies.” Surgical Clinics of North America, 1987; 67(6): 1153-80.