COCAINE AND EYE SURGERY

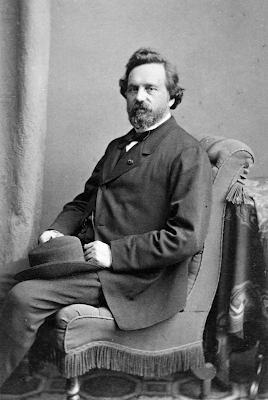

The time was early September, the year 1884, the place the famous Allgemeine Krankenhaus (General Hospital) in Vienna. Two house officers, Sigmund Freud and Carl Koller, who occupied rooms on the same floor, were discussing cocaine. Freud, interested in neurology and psychiatry, had found it to be a remedy for depression and had used it liberally on himself to lift his mood. Both were

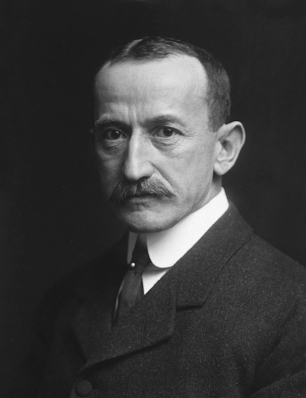

|

| Carl Koller (Wikipedia) |

aware that, placed on the tongue, it had a numbing effect, an old discovery. Freud had suggested recently to a friend, Leopold Königstein, a young ophthalmologist, that he try it locally in cases of trachoma. Königstein tried it but used a dilute solution mixed with alcohol, failing to relieve any symptoms.

Freud had just published an extensive review of cocaine and its uses (he mentioned the anesthetic effect on skin and mucous membranes but did not suggest any medical use in that regard), entitled “Über Coca.” He was also involved, with the help of Joseph Breuer, in the treatment of Dr. Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow, a physician addicted to morphine after suffering intense pain from neuromas complicating a thumb amputation. Based on reports from America of curing morphine addiction with cocaine, Freud and Breur attempted this therapy on Fleischl, though eventually with disastrous results.

Freud left Vienna in early September 1884, to visit his fiancée. Koller, intent on a career in ophthalmology, pondered the conversations on cocaine and suddenly decided to try its anesthetic

|

| Sigmund Freud (Wikipedia) |

effect on the eye. He went to the pathology laboratory, tried it on frog eyes, then on other animals, and finally on his own eyes and those of friends, finding in all cases complete anesthesia. Aware that the German Ophthalmologic Society was meeting soon in Heidelberg, and too poor to travel there on his own, Koller persuaded a friend, Josef Brettauer, to present his discovery. On September 15, 1884, Brettauer stunned the assembly as he exhibited a dog that remained indifferent while its cornea was pricked and rubbed by various instruments.

Reports of this miracle flew around the globe. Henry D. Noyes, president of the American Ophthalmological Society, witnessed the event and reported it briefly in the Medical Record the following

|

| Henry D. Noyes (Wikipedia) |

month. Another attendee of the meeting was the rising American surgeon, William Halsted, who began investigating cocaine as a local anesthetic on himself, eventually succumbing to an addiction he could not shake. His colleague, Richard J. Hall, who had performed one of the first appendectomies, joined him in self-investigations. He also developed an addiction, giving up his position at the College of Physicians and Surgeons to practice surgery in Santa Barbara. He died there, ironically, of appendicitis. Halsted and Hall obtained their cocaine from Parke-Davis, the first pharmaceutical company to have a laboratory staffed by scientists.

Herman Knapp, a German-born ophthalmologist in New York and founder of the Archives of Ophthalmology, not only praised cocaine’s use in eye surgery, he tried it in various other ways. He

|

| William Halsted (Wikipedia) |

injectied it into his urethra, after which he introduced silver nitrate (a treatment for gonorrhea) without pain. Ear, nose, throat specialists tried it successfully as a local anesthetic for their procedures. Ophthalmologists had used ether, of course, in surgery, but the after-effects, such as vomiting or restlessness, could endanger a recent eye operation. Globally, the price of cocaine shot up exponentially as patent medicine companies and tattoo parlors (to prevent pain) also made use of the drug.

Freud, on his return to Vienna, was chagrined that he had not thought one step further and tried it as a local anesthetic, either on the eye or elsewhere. Though Koller had made the breakthrough in Freud’s absence, Freud and Koller remained friends. Leopold Königstein, who had tried an inadequate cocaine preparation for trachoma, made a feeble attempt to claim credit, but Freud and the neuropathologist and psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg (who later received a Nobel Prize for treating neurosyphilis with malaria), persuaded him to retract his claim and credit Koller. Still later, Freud’s enthusiasm for cocaine turned to regret as its addictive qualities became more evident.

In spite of his instant fame, Koller’s future was insecure, for two reasons. He was Jewish and he had, in his daughter’s words, a difficult, tempestuous, personality. On top of that, a few months after his discovery, Carl had a fight with a colleague over the treatment of a hospital patient being admitted, for which he was challenged to a duel. Koller, though having no experience with foils, severely wounded his challenger. But he lost his chance at a university

|

| Franz Donders (Wikipedia) |

appointment since dueling was illegal. He managed to find a position in Utrecht, Holland, working with Franz C. Donders, creator of the tonometer and expert in the mechanism of accommodation, and Herman Snellen, creator of the Snellen eye charts used today (see essay of Aug 14, 2024). There he also befriended Willem Einthoven, father of the EKG. Two years later he was persuaded by Arthur Ewing, an American ophthalmologist whom he met in England, to move to America.

In New York, Koller established a thriving ophthalmology practice, married, and raised a family. According to his daughter, he regretted not having time for more research. His busy practice, an appointment to the Mount Sinai Hospital staff, and his duty as the first chief of ophthalmology at Montefiore Hospital occupied his time. Rewards came over the years, however, as he received numerous prizes for his discovery, including gold medals from the American Ophthalmological Society and the New York Academy of Medicine and the Kussmaul medal from the University of Heidelberg.

SOURCES:

Becker, H K (Koller’s daughter), “Carl Koller and Cocaine.” Psychoanalytic Quarterly 1963; 32 (3): 309-373.

Goldberg, M F, “Cocaine: The First Local Anesthetic and the ‘Third Scourge of Humanity.’” AMA Arch Ophthalmology 1984; 102: 1443-47.

Markel, H, An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the Miracle Drug Cocaine. 2011, Pantheon Books.

Spillane, J F, “Discovering Cocaine: An Historical Perspective on Drug Development and Regulation.” Drug Informat J 1995; 29: 1519S-1528S.

Hall, R J, “Hydrochlorate of Cocaine.” N Y Medical J 1884; 40: 643-4.

Lopez-Valverde et al, “The Surgeons Halsted and Hall, Cocaine and the discovery of Dental Anesthesia by Nerve Blocking.” Brit Dental J 2011; 211 (10): 487-87.

A full index of past essays is available at:

https://museumofmedicalhistory.org/j-gordon-frierson%2C-md