MEDICAL NOTES FROM THE

NEW WORLD

The tragic events following the arrival of Spanish colonizers in the Western Hemisphere are well known. The ravages of disease, including smallpox and measles, and abrupt social disruptions killed off large numbers of native inhabitants The new colonizers, though, had medical problems of their own.

The first voyage of Columbus, in 1492, from a medical point of view, was fairly uneventful. Illness was not a problem and the foods the crew encountered, including beans, cassava (yucca), peppers,

Christopher Columbus, by Sebastian del

Piombo, 1519 (Wikipedia)

potatoes, mangoes, pineapples, papayas, guava, passion fruit, and other vegetarian fare provided sufficient nourishment. Two ship surgeons, or fisicos, Maestro Alonzo, on Columbus’ caravel Santa Maria, and Maestro Juan on the Pinta, sailed with the expedition. Alonzo returned to Spain with Columbus while Juan remained with fifteen men to maintain a small fort on Hispaniola (now Haiti). Troubles began on the second voyage.

The second expedition, comprising 17 vessels, left Spain in September 1493. Aboard were about 1500 male colonizers, various animals including pigs, cattle, horses, dogs, cats, chickens (none of which were native to the Caribbean), and a variety of crop seeds. Many of the men came from noble families, seeking adventure or riches after having been idled following the final conquest of the Muslims in 1492. Illness broke out during the voyage, affecting both passengers and animals and continued to plague the colonists after arrival. The exact diagnosis is unknown, but symptoms included fever and extreme lassitude. Scholars have suggested diagnoses of swine flu, dysentery (some had diarrhea), typhus (believed prevalent during the final assault on Grenada), or a mixture of diseases.

Columbus himself suffered from the epidemic, called modorra, and was prostrated for weeks with weakness and inability to work. A physician in court service (médico de cámera), Diego Alvarez Chanca, attended him. Details of his life are sketchy. He probably received his medical education at the University of Salamanca, where the medical theory he learned would have been Galenic and his major text Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine. The more investigative approach to medicine, exemplified by Vesalius, was yet to come. Chanca, an adventurous man, actually volunteered to go with Columbus.

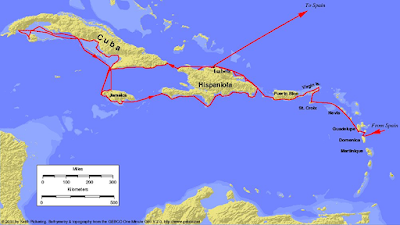

Map of second voyage (Wikipedia) Click to enlarge.

Chanca, in a letter back to Spain, gave some idea of local problems, but he provided no further insight into the diagnosis of the epidemic disease. Disease entities as we know them had not entered the medical vocabulary. He worked hard and Columbus praised him for his efforts to aid the sick.

Famine accompanied the epidemic. The initial crops of the Spanish colonists grew poorly, provoking the Spanish to steal from the Hispaniola native Taíno. Attempts to enslave natives or otherwise maltreat them led to hostilities that reduced the food supplies of both groups. Hunger and starvation, lowering resistance to disease, drastically drove down the population of Spaniards and natives alike. When Columbus returned to Spain in early 1494, over half of the original 1500 colonists and untold numbers of Taíno had perished. Reports of illness with superficial ulcers appeared, perhaps the first recognition of syphilis, considered a “new world disease.” The surgeon of the previous trip, Maestro Juan, and the fifteen men left with him had all perished, probably killed by local natives.

Columbus searched for spices as well as gold. He and Dr. Chanca identified plants they thought were varieties of aloe, pepper, and cinnamon. They were incorrect, though some plants proved useful as medicines. The spice they labeled “cloves” was allspice, so named because its odor suggested a mixture of clove, cinnamon, and nutmeg. And they found tobacco.

By the 1500s, colonizers and adventurers were arriving in larger numbers, both on the islands and the mainland. Various febrile diseases, probably including malaria, were now common, though no diagnoses familiar to us appear. Smallpox arrived in the Caribbean in 1518. The native population, never exposed to it and already in severe decline, suffered severely while the Spanish population, maintained only through new immigration, had fewer losses. In 1520, smallpox reached Mexico, imported by an expedition sent

Hernán Cortés, 1525 portrait

(Wikipedia)

from Cuba to arrest Hernán Cortés for disobeying orders. Cortés had attacked Tenochtitlán (now Mexico City) but had been forced by Aztec forces to withdraw. He was licking his wounds when smallpox intervened and devastated the victorious Aztecs, reducing their numbers and killing their leader. Cortés took the depopulated city back, another example of disease affecting history. Smallpox went on to devastate Central and South America, ravaging whole populations.

Smallpox in early America, from Florentine Codex

(Wikipedia)

The first documented epidemic of measles broke out in 1532, though reports suggestive of its appearance surfaced as early as 1529. Measles, highly infectious, swept through the colonies rapidly, causing many more deaths. In all the outbreaks of disease mentioned, the combination of Spanish disruption in the daily life of native Americans, slavery, work conditions, and the falloff in the ability to farm and prepare food, produced widespread famine and lowered resistance to disease, all contributing to the terrible mortality.

More epidemics plagued the Spanish possessions, though their nature is often obscure. Two deadly epidemics, in 1545 and 1576, of a new disorder, known in Nahuatl as cocoliztli, killed up to 80% and 50% of the native population respectively. Symptoms included nosebleeds, hemorrhagic phenomena, diarrhea, and fever. Recent studies suggest they might have been due to a virus related to today’s arenavirus or hantavirus (“four corners virus”) species, carried in rodents. Both outbreaks followed periods of severe drought.

Much is unknown about the early medical problems of the Spanish New World and will probably remain so. But it is clear that epidemics and death flourish in times of food shortage and/or severe social disruption, even today.

SOURCES:

Cook, N D, Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest. 1998, Cambridge Univ Press.

Gonzalez, J P H, “En Torno a Una Biografía del Primer Médico de América Diego Álvarez Chanca (circa 1450 – post 1515).” 2012; Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos 58: 29-49.

De Ybarra, A M F, “ A Forgotten Worthy, Dr. Diego Álvarez Chanca, of Seville, Spain.” 1906; JAMA 47 (13): 1013 17.

Acuna-Soto, R et al, “Megadrought and Megadeath in 16th Century Mexico.” 2002; Rev Biomed 13: 289-92. (also in Emerging Infectious Diseases 8 (4), 2002, available at: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/8/4/01-0175_article)

Griffinhagen, G B, “The Materia Medica of Christopher Columbus.” 1992; Pharmacy in History34(3): 131-45.

A full index of past essays is available at:

https://museumofmedicalhistory.org/j-gordon-frierson%2C-md