A FAMOUS NAVAL HOSPITAL:

HASLAR

By the mid-eighteenth century, Britain had established colonies around the world. To protect the new possessions and maintain the trade routes that rendered the colonies profitable required an expanded navy. Larger ships, into which hundreds of crewmen were crowded in close quarters, sailed ever-longer routes far from land. Though the seamen’s diet, measured in calories and meat content, was richer that that found in most homes at the time, it did not included perishable fruits or vegetables.

The diet rendered the crews susceptible to scurvy, brought on by the lack of vitamin C, and the killer of more men than combat wounds and other diseases combined. Crowding also permitted infectious diseases to flourish. Among the latter, typhus was the most common, though smallpox and yellow fever appeared intermittently.

In the early years of naval expansion, the sick arriving in a port were placed in homes, lodging houses, or small private hospitals contracted to care for them. Such a system, however, failed. Fraud was rampant; the host facilities padded the bills and provided minimum care. Alcohol was traded for clothing and the few contract doctors available were often busy with private patients. Faced with over 15,000 men yearly invalided ashore, the Navy decided to build substantial hospitals to provide better care. The largest, Haslar Hospital, went up across the bay from Plymouth, home of the Navy’s principal docks.

Originally designed as a large four-sided building around a large square central court, only three sides were constructed to allow more ventilation. The central portion was primarily for

|

| Plan of Haslar Hospital (from Tait, History of Haslar Hospital) |

administrative functions (the administration was civilian) and the side wings featured double pavilions three stories high and separated by a small, aerated area. The building opened in 1754, allowing accommodation for 1200 patients, and was the largest brick building in England and perhaps in Europe. Lighting was by gas, replaced by electricity in 1905. Water closets were installed at the end of each ward, and sewage emptied into Portsmouth Harbor via a nearby creek. Wells supplied fresh water. The first chief physician was James Lind, a civilian at the time.

|

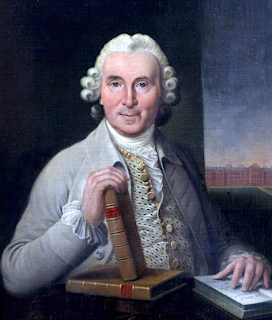

| James Lind (Wikipedia) |

Lind was a Scot who learned surgery as an apprentice and went to sea as a surgeon’s mate at age 23. While serving in the Channel Fleet he conducted his famous trial of remedies for scurvy, noting that the most effective curative was juice from lemons and oranges. He then left the Navy to earn an MD degree at Edinburgh, entered private practice, and found time to write A Treatise on Scurvy, published in 1753, in which he detailed his success with citrus juice to prevent scurvy. Strangely, though, Lind did not emphasize citrus juice for the treatment of scurvy, believing it to have other causes. Lind held the post at Haslar until 1783, succeeded by his son.

By the time of the American revolt against England, Haslar held 2100 patients, making it four times the size of Guy’s Hospital in London. Not all seamen wanted to be there. Many had been impressed into service out of prisons or poorhouses and frequently escaped during the night or had alcohol smuggled in. To discourage desertion, bars were put on the windows, a wall twelve feet high surrounded the hospital, and guards patrolled outside. Yet in1794, 226 still managed to escape. Nursing care was unreliable, with alcohol often bartered for clothing, and sometimes nurses or attendants coaxed sick patients into willing their property over. Mortality overall was substantial. In 1780, 909 deaths were recorded.

The few doctors assigned to the hospital were allowed to engage private practice and when needed might be miles away with a patient. Only after 1797, was private practice forbidden. At first, surgeons operated without anesthesia on the wards, but after patients objected a separate operating room was installed. Surgeries were infrequent, however, until the arrival of anesthesia in the 1850s.

In the early days, scurvy and typhus were the most common medical problems in the hospital. Typhus most commonly broke out on a ship after men from jails or from other ships carrying typhus were put aboard as crewmembers. Most medical men considered it “contagious,” not recognizing the role of the louse in its

|

| Thomas Trotter (Wikipedia) |

transmission. Thomas Trotter, appointed Physician to the Hospital in 1793, improved hygiene enormously. New patients were bathed (as before), shaved, their hair cut short, and given clean clothes. Thereafter they were washed daily and given twice-weekly changes of hospital gowns, which undoubtedly helped prevent new typhus cases. Trotter halted the treatment of bleeding for fevers and supplied a rich diet, speeding recovery. By this time, the value of fruits and vegetables for scurvy was evident. Trotter also revised the administrative structure, pleaded for more personnel to attend the sick, and recommended that the Navy take over the previous civilian administration.

The Navy did assume responsibility for the hospital and introduced a teaching program aimed at medical problems peculiar to shipboard life. Courses in new subjects, such as bacteriology, were introduced. Anesthesia allowed a more active surgical service. The hospital, over time, cared for casualties from the Napoleonic wars, the Crimean War, and both World Wars. The country’s first blood bank opened there in 1940. The National Health Service took over the site in 2007 and closed it in 2009. The hospital now contains flats for retirees. Over 10,000 bodies are believed to be buried on the grounds. Forensic scientists have recently examined a few skeletal remains and documented osseous signs of scurvy, once a persistent threat to a seaman’s life.

|

| Modern view of the hospital, showing a guard tower (Wikipedia) |

SOURCES:

William Tait, A History of Haslar Hospital, 1906; Griffin & Co.

Kenneth J. Carpenter, The History of Scurvy and Vitamin C, 1986; Cambridge Univ Press.

Bryan Vale and Griffith Edwards, Physician to the Fleet: The Life and Times of Thomas Trotter. 2011; Boydell Press, Woodbridge.

James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, 3rd ed. 1772; London.

Eric Birbeck, “Royal Naval Hospital Haslar: Paragon of Nautical Medicine.” The Grog Ration 5 (2): 2-5, 2010.

Eric Birbeck, “The Royal Hospital Haslar: from Lind to the 21st century.” The James Lind Library, accessible at: https://www.jameslindlibrary.org/articles/the-royal-hospital-haslar-from-lind-to-the-21st-century/