CHRISTMAS DISEASE

In the final issue of the British Medical Journal for 1952, an article appeared with the intriguing title: “Christmas Disease: A Condition Previously Mistaken for Hemophilia.” The authors described a new bleeding disorder found in seven patients. Case number one was a five-year-old boy named Christmas (not stated if this was a first or last name), who had suffered several bleeding episodes after play-induced injuries. All seven cases were indistinguishable from standard clinical hemophilia except that, strangely, bleeding could be stopped by transfusion of plasma taken from hemophilic patients. The authors explain the name given to the disorder, noting that the practice of naming diseases after patients was introduced by Sir Jonathan Hutchinson and had the advantage that “no hypothetical implication is attached to such a name.”

Jonathan Hutchinson was born into a Quaker family in northern England. He was apprenticed briefly to a local doctor, attended Jonathan Hutchinson (Wikipedia)

medical school in York, and, in 1850, finished medical training at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. There he befriended other Quakers, such as Thomas Hodgkin, Joseph Lister, and Wilson Fox (later physician in ordinary to the queen), the latter two still in medical school. He became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons and opened a practice. He joined the staff of the Royal London Ophthalmic Hospital, where one of his assistants was Warren Tay, first describer of Tay-Sachs disease, and he attended at the Blackfriar’s Hospital for Skin Diseases. In this way he accumulated broad clinical experience, earning a reputation as a “generalized specialist.” He became an authority on syphilis, wroting a large book on the subject, and created the Archives of Surgery, a journal lasting a decade that was truly his own since he wrote virtually all the articles.

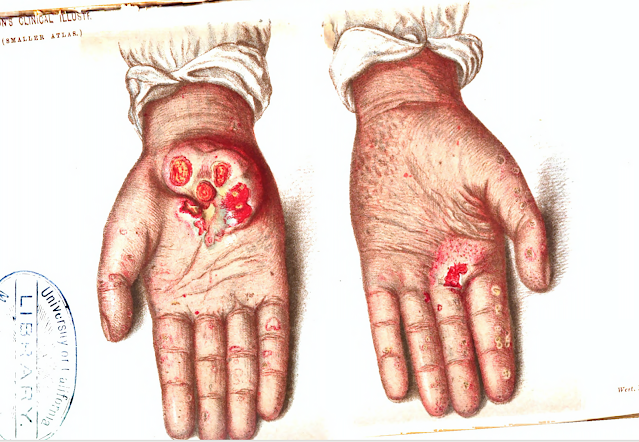

Skin cancers arising in arsenic-related keratitis (from Hutchinson's Archives of Surgery,

1890, v 2. (Hathi Trust)

With a friend, he resurrected the expired Sydenham Society as the “New Sydenham Society.” It brought translated European medical works (and writings of British authors) to British doctors. He persuaded the British Medical Association to open a medical museum, edited the British Medical Journal for a time, and even opened his own private museum (focusing on natural history), a sign of his passion for collecting. He started a postgraduate school where practitioners, from home and abroad, could be brought up to date on the latest findings. This endeavor floundered, however, from lack of interest.

He is known for two failings. Although a keen observer and ardent collector, he did not investigate, as did the great surgeon and collector, John Hunter, with whom he was often compared. Secondly, he inexplicably insisted that leprosy was caused by the consumption of spoiled or rotting fish, even after the discovery of the causative organism was widely accepted. The breadth of his clinical acumen is what impressed colleagues, though. He was, as William Osler put it, “the last of the polymaths, the man at home in all spheres of medical practice.”

What about naming diseases after patients? Hutchinson, an astute observer, is said to have published over 1000 case reports and, indeed, many contained names coined after patients. Examples are Mortimer’s malady (later considered sarcoidosis), Penman disease, Hilliard’s lupus, and Branford legs. Readers of his reports often reversed the process and invented eponyms in the Hutchinson name. “Hutchinson’s triad” is known to medical students as designating three features of congenital syphilis, one of which is “Hutchinson’s teeth,” (notched and small central incisor teeth). Hutchinson’s facies, Hutchinson’s angina, Hutchinson’s patch, and others placed his name for posterity in various publications.

But back to Christmas disease, which is of great historical interest. As knowledge of genetics and hematology progressed, “Christmas disease” took the name factor IX deficiency or hemophilia B, a sex-linked recessive bleeding disorder carried by females but affecting males almost exclusively. It constitutes about 15-20% of hemophilia cases. This disorder was a burden on royal families, the afflicted males all descending from Queen Victoria. Queen Victoria’s granddaughter, Princess Alexandra, married to Tsar Nicholas II of the Romanov family, had a son, Alexei, heir to the throne, who bled easily. The family's

The mutation exerted tragic effects on descendants of Queen Victoria. One son, two grandsons, and five great-grandsons died of excessive bleeding. The remaining great-grandson, Alexei, was murdered before the disease took its course. One can only speculate on what other avenues history might have taken if the family had not been plagued by the bleeding disorder. Victoria’s own son, Leopold, grew old enough to marry and have a child, but at age 30 he had a fall, dying while his wife was pregnant with their second child. Prince Maurice, son of Victoria’s daughter Beatrice (a known carrier), died on the front in WWI, and probably did not have the disease, or at most a very mild form. No antecedents to Queen Victoria with the altered gene have been discovered and it is presumed that a spontaneous mutation occurred in her genes or those of the immediate prior generation.

But enough of this melancholy narrative on Christmas disease. More joyfully: Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays to all!

SOURCES:

Biggs, R. et al, “Christmas Disease: A Condition Previously Mistaken for Hemophilia.” Brit Med J, 1952; Dec 27: 1378-82.

Van Ruth, J and Toonstra, J, “Eponyms of Sir Jonathan Hutchinson.” 2008; Int J Dermatology 47: 754-58.

The Moscow Times, July 16, 2018 (online at: https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2018/07/16/investigators-confirm-authenticity-tsar-nicholas-ii-body-burial-site-a62263

Anon., “Case Closed: Famous Royals Suffered from Hemophilia.” Science Oct. 8, 2009.

Ellis, H, “Jonathan Hutchinson (1828-1913).” J Medical Biography 1993; 1 (1): 11-16.

Godlee, R., “Sir Jonathan Hutchinson, F.R.S., 1828-1913.” Brit J Ophthalmology 1925; 9 (6): 257-81.

Ewing, M., “Jonathan Hutchinson FRCS.” Ann Roy Coll Surg 1975; 57: 296-308.

Rogaev, E.I., et al, “Genomic Identification in the Historical Case of the Nicholas II Royal Family.” Proc Nat Acad Science (early edition), 2009; 106 (13): 5258-63. Online at: https://www.pnas.org/content/106/13/5258